All African People’s Consulate Curatorial Statement

Dread Scott and the All African People’s Consulate

2024 La Biennale di Venezia: Stranieri Ovunque

Homeland Insecurities

American artist Dread Scott chose his pseudonym as a dark pun, assuming the mantle of the enslaved man Dred Scott and the 1857 US Supreme Court ruling which stated that his living in a free state and territory did not entitle him to his own liberty because he was another person’s property, a Black man “so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” as the decision reads. Like many Black Americans, the Dread Scott is the product of migrations; the forced migration of slavery that brought his ancestors to North America as chattel, and at least one more that brought his more immediate family to the Midwest during the period of the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when many Black Americans moved from the south to escape Jim Crow apartheid and to seek economic opportunity.

Scott hails from the American Midwest, the nation’s “heartland,” the north-central third of the country, whose inhabitants are known for an earnest but plain-spoken directness. From a certain vantage, Scott’s work can be seen to reflect this seemingly no-nonsense, “it is what it is,” sensibility. Of course, what it is is rarely uncomplicated, for an Illinois farmer or for a Chicago-bred Black artist. But Scott’s superficially “literalist” approach allows the content of his examinations and critiques to emerge with a clarity that more “artful” outward forms and structures might obfuscate.

Much of Dread Scott’s performance-based work could be assigned to the branch of artmaking often called “relational aesthetics.” This approach relies upon the social context and the ensuing interactions of those present, within the contrivance of an artist-created event, for its effects. The audience-participant boundary is erased; everyone in attendance becomes an element in the work, which is often characterized by a literal directness. One artist famously cooked a meal for a group of people in a gallery setting as the work itself. On at least one level, it is just what it is. For some art-watchers, these events are bemusing, without sufficient structure, purpose, or resonance, or at least not enough to make them something other than meals in slightly unusual venues. But in Dread Scott’s performance works, form typically takes on firmer contours and clearer structure, lending greater transparency and purpose to what actually transpires within its parameters.

From his emergence as an artist, Dread Scott’s performance work has hinged on the bodily inhabitation of the works’ conceptual core and the visceral responses of those performing it, whether it is the artist himself (On The Impossibility Of Freedom In A Country Founded On Slavery And Genocide, 2014); a surrogate (White Man For Sale, 2021); or the unprepared viewer-participant (What Is The Proper Way To Display A US Flag?, 1988). To revitalize the experience of resistance and the fortitude of 1960s Civil Rights protestors, distanced from us by time and the grain of iconic black-and-white photos, in On The Impossibility Of Freedom, Scott engaged a fire department to provide the considerable aqueous force – between 200 psi / 1,380 kPa and 300 psi / 2,070 kPa – to re-embody the experience of standing up – literally – against the oppression of codified and the violence of white terrorism that enforced it. To revisit and manifest the trauma of the sale of Black human beings as slaves in the antebellum American south, Scott updated the grotesque mercantile ritual for the digital present, and “sold” a middle-class white man as a chattel NFT “on the block” in a Christies auction, for White Male For Sale. (In a perverse-poetics, NFTs utilize the unintentionally apt and resonant term, “blockchain,” for the digital technology assuring the inviolable integrity of the provenance of the “property.”) Scott’s employment of the obverse, of the apparently simple substitution exemplified in White Male, demonstrates the profound utility of this transparent and seemingly guileless maneuver. By replacing a Black person in this historical tableau with a contemporary white counterpart, a move so obvious – after its been made – but still so startling to many, Scott also provides a ground-level basis for empathetic and equitable relations among people. What if the person on the block was your mother, father, sibling, lover, friend? What if it was you? But for us to occupy that position mentally and emotionally, first we need to dispense with some of our invented hierarchies, beginning with the most obvious ones, those based on the fiction of race and the appearance of “color.” These should be the simplest things in the world to eliminate, but judging from the human record, they are among the most intractable. So, while Dread Scott’s work in performance, at first glance verges on the literal, its echoes, reverberations, and resonances sound depths beneath the often frozen-seeming surfaces of time’s images, and the flattened distance of dispassionately related and selective “histories.”

Past Contemporaneous

Derek Jarman’s 1986 film Caravaggio creates an anachronistic, fictionalized “history” by introducing contemporary intrusions – car horns, the sound of mopeds, cigarettes, modern clothing, radio chatter, a view of a car – into the otherwise Baroque time-space of the artist’s life and work, echoing and carrying forward the artist Caravaggio’s contemporization of dress and setting in his paintings of biblical and historical themes. It’s a sort of Steampunk rooted in an age before steam. Caravaggio’s dramatic and of-the-moment deployment of chiaroscuro in his paintings signals the theatrical and artificial nature of his approach. The aesthetics of Caravaggio’s enterprise question and investigate the notion of time, presenting it in intersecting streams or overlaid planes, making the past as real as now while making our grip on now as fugitive as the past. This is very different from productions of Shakespeare plays or Mozart operas performed with modern dress or within contemporized settings. Those approaches offer coherent alternatives to the original period contexts. Jarman’s Caravaggio (and the artist Caravaggio) create consciously disjunctive settings, where the period-historical and the contemporary do not fully cohere, where their juxtaposition functions as an intentional form of simultaneous contrast which unsettles and displaces us.

Dread Scott’s Slave Rebellion Reenactment (2019) echoed Jarman’s approach, while applying it to different, more urgent socio-political ends. To address, interpret and force an acknowledgement of an historic (and in all senses historically suppressed) event, Scott recreated it. He, with hundreds of participants, reimagined the 1811 uprising of enslaved people in Orleans Territory, in what is now the US state of Louisiana, as a reenactment of the original event, focusing on the seminal importance of the spirit of the rebellion. Seeking to portray it with a veracity greater and more complex than the codified version that has been handed down Scott, like Jarman, employed anachronistic elements to his conceptual ends; Afrofuturist mixings of contemporary dress and historically meticulous attire and armaments, the projection of an historical event into a contemporary time-space. The reenactors marched the same 24 miles of the German Coast pathway as their rebellious ancestors to New Orleans – but while wearing Adidas, Nike’s, wristwatches, and modern eyewear – past the gated communities, trailer parks, strip malls, and petrochemical facilities (in which some of the reenactors likely worked) that have supplanted the sugar cane plantations where their ancestors were forced to labor. While Jarman’s film makes new art from an historical artist’s notorious, tempestuous life and radically new painting, Scott’s undertaking makes new art from an existential but quixotic effort to pursue a radical independence by forming a Black free state adjacent to the Anglo-centered United States of the time.

Degrees of Africa

The process of creating the All African People’s Consulate (AAPC) as a Collateral Event for the 2024 La Biennale di Venezia: Stranieri Ovunque, involved conversations among many of Dread Scott’s collaborators and peers. In 2022, Scott’s 1988 work What is the Proper Way to Display a US Flag was included in the exhibition Globalisto. A Philosophy In Flux, at the Museé d’Art Moderne et Contemporain, Saint-Étienne Métropole (France), curated by Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape (Mo Laudi; a multidisciplinary artist, curator, composer, DJ, living between South Africa and Paris). The spirit and aspirations of the AAPC project, including its focus on what Laudi has called “radical hospitality,” were voiced in a recent Zoom conversation, presented here in edited form, between Mo Laudi and Dread Scott.

Dread Scott:

The Globalisto philosophy and exhibition recently influenced my thinking. It was a really important show, both the exhibition itself but also the library that you had there and the symposium which brought many artists in the show, curators and scholars together. I thought that the mastermind behind it would be an excellent person to talk to in relation to the All African People’s Consulate, a conceptual artwork which is an official Collateral Event during the 2024 Venice Biennale, the creation of a consulate for an imagined afro-futurist, pan-Africanist country / union of countries.

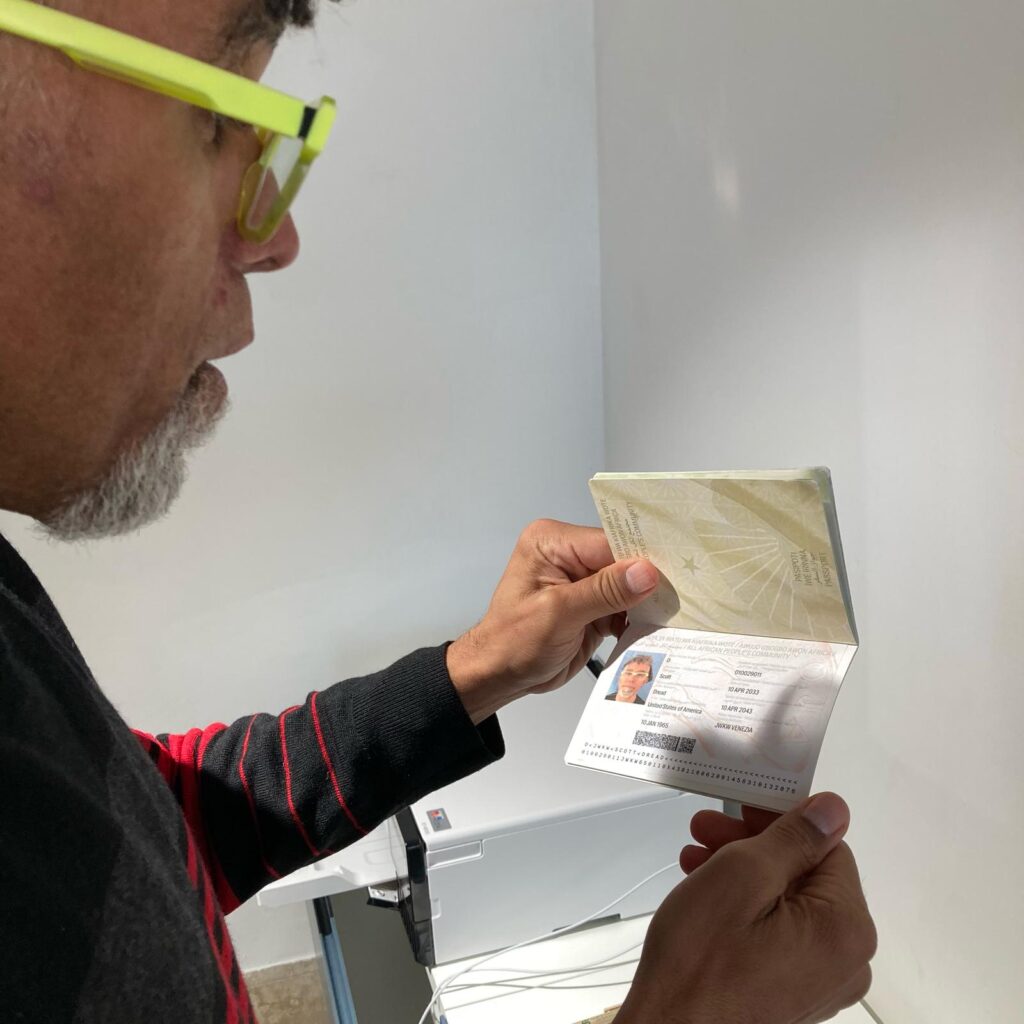

The union of countries that it exists for doesn’t exist, but the consulate will be real. People will come to this place and if they’re of African descent, they can apply for a passport and they will receive one. If they are not of African descent, they can apply for a visa to visit this place. People will be interviewed and the conversations that are had with the people that apply will be different. If you’re applying for a visa, if you’re from a country that has had a colonial relationship with Africa, you will be asked if you renounce that colonial heritage. If you want to come and chill and be part of this radical new future, then great, you’re welcome. And if you’re living in Africa or currently an African national in one of the countries, or if you’re Black in any way, shape or form, whether you live in Jamaica, whether you live in the United States, whether you live in France, you get a passport—one with your picture in it, that looks just like a real, bona fide, legitimate passport. And if you’re not of African descent, you can apply for a visa.

This is the future and this is a pan-Africanist, globalist vision.

Historically, whenever our labor was needed, we were dragged wherever capitalism wanted us. And now, they say we can’t come. And so I thought that creating a consulate in the midst of this important art exhibition would invert the logic where African movement is controlled and restricted. And importantly, this project will create community amongst people coming to Venice, especially if they’re Black, if they’re African or African descent, this is going to be like a welcoming and a gathering. It will be fun, it will be cool and it will be a place to think about the present and think about the future.

Mo Laudi:

It’s really powerful to conceptualize this idea. And obviously I love how you connect this to Globalisto. Globalisto is a philosophy to consider how we think about ourselves, how we think about history, challenge it and its impositions, interrogate the borders that we live within, created by colonialism, by Westerners. These borders exist to this day in Africa. How do we move around and have different races and diaspora connected? As an African traveling to Europe, I was surprised to find the experience is not the same for Europeans traveling to Africa… The role reversal you are proposing questions this ingrained ideology that we now still just live with. And how did you come up with this concept?

DS:

Black people in Venice are not always welcomed, and in Italy in general with the rise of the current government, there are real barriers to people especially crossing the Mediterranean, and Italy basically forces people to drown by erecting these really serious barriers. Yet people are still coming.

The space that Wake Forest (where the curator for the project is based) had in Venice used to be the US Consulate. For a range of reasons, the venue changed but the idea of creating this consulate had already emerged. I was thinking about the presence, the historic and long-term engagement and exchange of cultures, particularly between Africa and Europe. And yet now, we tend to think that the mingling and crossing and intersection of cultures is a modern thing.

And in this particular Venice Biennale, which is called Foreigners Everywhere, the question of migration is at the core. The All African People’s Consulate challenges the traditional notions of state and citizenship.

So this is a challenge to the art world to embrace an expansive culture that is actually part of a broader culture that makes for a much more rich and complex dialogue and discussion.

ML:

It seems so pertinent to have had your starting point in what used to be the US Consulate. The role of the US is complicated in the world with all its strategically positioned military bases. Even now, they’re thinking of constructing a new military base in Lesotho, which is basically the country in the middle of South Africa… It’s all about control. How does your work move from How to Display an American Flag to the Consulate?

DS:

America is a country that was founded literally on slavery and genocide. America talks about itself as this democracy but in reality, it captured and enslaved people from one continent to work the land that they stole from peoples on another. That’s what America is. It extends that brutality around the world. Since 1899 it has been occupying, interfering with, invading, conquering—from Puerto Rico to Cuba to Haiti to South East Asia, and installing and propping up dictators in Africa, South America, and the Middle East. And so it’s very easy to move from thinking about What is the Proper Way…?, which invited an audience to question what the United States is, what patriotism is, to getting towards a Consulate which actually says, let’s bring together some of the people who’ve been affected by colonialism and actually celebrate the rich history and diversity and complexity and culture that’s being ignored, crushed, destroyed, distorted, and try and strengthen and build community in opposition to that.

ML:

How to Display an American Flag is such a powerful work, it became so controversial, even to the point that it was talked about in the Congress. How do you feel that the AAPC would engage in a way that it grows from being an artwork. How would people carry the experience of the work after being in the space?

DS:

I do very much think about how do people move from an art world context where art can be just thought of simply in aesthetic terms, to touching you more in your soul, in your heart.

And I think that this project, it somewhat builds on a project I did in 2019 called Slave Rebellion Reenactment, which reenacted the largest rebellion of enslaved people in the history of the United States. We had 350 reenactors that marched for two days, covering 24 miles on the outskirts of New Orleans. We were in period costume from 1811, when this rebellion happened, and we marched with sickles and sabers and muskets and machetes.

Many people who saw the work in their neighborhood were really excited and inspired. Others were challenged by it.

ML:

How will this new project compare to the Slave Rebellion Reenactment?

DS:

Both projects really connect people. Let’s say you’re from Kenya living in Venice working, let’s say you are one of the people who cleans up in a restaurant or something like that. And you are made to feel not very welcome, and you’re often looked down upon. Maybe having this community embrace you — you get a passport that says you’re part of this broader community — I think that’s really important.

And then you meet other people that are in a similar situation, or perhaps somebody visiting that’s in the art world that perhaps is from Martinique. And that builds a community in a way that’s similar to what Slave Rebellion Reenactment did—for the reenactors.

With the AAPC, it is going to be something which people internalize and build on. It’s figuring out what people in that area need, whether it’s a community for people who are just visitors to Venice who are coming to see an art fair and they need a place to chill and hear some Burna Boy or Kabza De Small or get info on a place to get Ethiopian food or perhaps it’s connection to legal advice for migrants?

ML:

As an African American, how do you approach the question of appropriation? You are engaging with an African subject matter. Can this be perceived as a problem or is this exactly what you want to challenge?

DS:

I think that’s a really good question and part of what people should be talking about with this project. Some people should be like, “Dude, you’re not from Africa. How can you do this?” And in thinking about this, I’ve been thinking about Marcus Garvey a bit. He proclaimed himself the President of Africa, yet he’d never been there. I don’t want to be that guy. But the thing that’s funny is, Garvey’s Black Star movement is what inspired Kwame Nkrumah and the newly independent Ghana to put a black star on their flag.

The diaspora is complicated and it’s real. Africa today wouldn’t exist the way it does without the diaspora, and much of the diaspora is created by enslavement and that whole legacy. Africa has been formed by that. And those of us in diaspora are part of that connection to that history and that continent. And yet, there is a way in which a lot of times, African Americans in particular, have appropriated African culture. There’s this really interesting book by Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother, where she goes to Ghana, actually, somewhat expecting, “Hey, the people of Ghana will embrace me. I’ve come home.” That’s a bit of a conceit of the work, but it is really wrestling with the fact that both there is this real connection to the continent but also a real separation. The people of the continent in Ghana, in Nigeria and South Africa, aren’t thinking about us African Americans all that much.

But, on the other hand, years ago, Fela was interviewed and somebody was talking with him about his music and saying, “Look, you seem to be influenced and inspired by James Brown.” And he said, “Well yeah, but actually I’m more inspired by Malcolm X. In fact, I want to be Malcolm X.” And here was this badass Nigerian artist that’s at the height of his powers, and he was saying this African American who was forged in the United States had developed a political understanding that influenced him.

I hope that in doing a project like this it isn’t thought of as appropriation but a dialogue amongst Africans, on the continent and in diaspora. How do we think about this? What do we need? How do we come together and how do we not appropriate but actually exchange ideas and learn from each other?

ML:

Absolutely. The foundation of Globalisto was exactly that: how do we interconnect? How do we create this community globally? Looking at all these borders that have been created and how can we eradicate them, the way that Achille Mbembe asks, “How do we think of a border-less world?” I am interested in how the student revolution in South Africa was inspired by the Black Panther movement, all that was happening, and then those politics of I’m Black and I’m proud coming back in to inspire the students in South Africa and the students creating a rebellion. And then you see, even Malcolm X’s trip in Algeria in 1969, how he gets inspired by what was happening in Africa at the time. Martin Luther King invited by Kwame Nkrumah, What was being said between Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba as they were moving around different African countries. At that time she didn’t have a passport and she was banned from returning to South Africa. How does this community continue after?

DS:

I wouldn’t be the person I am, the political person I am, without South Africa, without the anti-apartheid movement. I was really inspired in 1985, ’86 by that, and particularly I was checking out Steven Biko and reading about the Black Consciousness Movement. That was my early, young political foundation.

And then later in life, even as recently as Globalisto, seeing the library that you created and seeing Drum Magazine and things like that. This exchange is happening somewhat organically. And I think part of what this project is, is trying to both acknowledge that and concretize it, and give it a form. Passports have pictures in them that tend to tell the story of a country. And so there are going to be images of everything from the pyramids in Giza, to Great Zimbabwe, to the Timbuktu manuscripts, to Toussaint Louverture. It’s going to be this book that will tell 5,000 years of African history, the whole Continent and diaspora. It’s bound to fail but it will be really interesting.

The passport will live on, and the conversations that we have will live on. Imagine if you’re from Kinshasa and you come to this show and you see this consulate and you’re like, “They’re talking about border-less, frictionless movement within Africa. Yeah, why don’t we have that?” And what does it mean if people from Mali hear about this and say, “We’ve already been talking about that, but let’s accelerate that conversation. How do we make it easier for somebody from Mali to go to Ghana or to go to Nigeria…?”

ML:

Can you imagine it is actually much more expensive and much more difficult to fly from South Africa to Ghana than to fly to Paris? People have to apply for a visa as well.

I am ruminating on how objects in Africa were extracted, like masks and sculptures and artifacts and they were numbered. Initially they were stolen by various people including the British army, and ended up in European museums. I am fascinated that most of the names of the actual makers never made it into the history books. These objects traveled through Europe and, even now, materials such as sugar, cocoa, gold, diamonds and platinum travel easily. Yet bodies are a completely different question. People actually die crossing the Mediterranean. How does the Consulate address these issues?

DS:

I think that what you hit on is actually the state of the world. Capitalism and colonialism made it very easy for money, resources and capital to travel seamlessly. And law and policy and armies were set up to make that happen. But people were tightly regulated, and that legacy continues to today. The AAPC actually implicitly challenges that whole notion and is bringing together the types of people who will be part of upsetting, turning over and changing that.

ML:

We find ourselves, perhaps always, in the midst of a constant aesthetic enunciation, where the very act of living and breathing is a performance, a poetic gesture towards the possibility of a future. Yet, this aesthetic lingering, this continual poeticising of existence, begs of us a question, a demand, to shift from the ethereal to the earthly, practical from ideation to action. It’s beautiful how your work traverses this terrain, from the metaphysical musings to questioning the concrete streets of the social, the political.

There are Black People in the Future Even Now

By creating the All African People’s Consulate (AAPC) in Venice as part of the 2024 La Biennale di Venezia: Stranieri Ovunque, Dread Scott engages in another apparently simple act of reversal or inversion. Our media feeds are replete with images of Black people engaged in violence, often against one another, in desperate migrations across hot, dry places, or in frequently disastrous situations aboard overcrowded, leaking rafts crossing the Mediterranean. These people almost invariably pictured as trying to leave a dysfunctional Africa. But the AAPC offers a riposte to prevailing views of the continent, its peoples and its possibilities. What if, instead of being seen always as a place to escape from, there was an African community of nations which was a magnet, a select destination for immigration, visitation, and tourism? Not too long ago this conjecture would have been resoundingly dismissed by those in “advanced” nations like the US. But who’s laughing now, after one of the world’s oldest democracies nearly destroyed itself in an autocratic attempt to overturn a fair election – the most scrutinized in its history – and is setting itself up for an even more viable attempt at dictatorship in 2024? It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to visualize oneself wanting to leave such a place. The EU overall is moving closer to its most extreme members’ draconian, antidemocratic stance vis a vis the world and even their own citizens. The AAPC offers a different option, one hoped for by the Black freedom fighters of 1811 Orleans Territory, and by some 1960s Black activists: a free state for “Africans,” truly independent and democratic. Visionary Afrofuturist and musician Sun Ra famously proposed that “space is the place” – the locus for free Black people of the diaspora to reconvene. But what if we didn’t have to go that far? What if it was possible to achieve on this planet? What if Africa was that place? What if it always has been?

In the AAPC you can apply for an All African People’s Community passport, or visa. For those of African descent the AAPC facilitates your citizenship in a possible place and situation, one not yet achieved except in this present outpost of a future. For others, a visa allows you to visit.The premise of the AAPC is the opposite of most existing diplomatic and immigration choke-points; while those often function to constrain your admittance and movement in an effort to keep you out, the AAPC facilitates ways to let you in. In a convivial, celebratory setting, you are invited to stay, converse, and interact in organic, spontaneous, unsurveilled ways. As you wait in the AAPC for your appointment to get your document you may also ponder the humanizing fact that thousands of years ago, all of our ancestors began to move, to “emigrate,” from Africa and out into the entire world. And just as very early Venice was a refuge for those escaping the disintegrating imperial Roman world, during the 2024 La Biennale di Venezia: Stranieri Ovunque (in a city where most of us are “strangers”), the AAPC can be a destination and sanctuary. Welcome home.

Paul Bright

Director of Art Galleries and Programming

Wake Forest University

2024